Durnan’s greatness for Canadiens recalled 60 years after Hall induction

Durnan’s greatness for Canadiens recalled 60 years after Hall induction

Goalie Week spotlight shines on ambidextrous keeper, 1 of 100 Greatest NHL Players

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

Welcome to Goalie Week. NHL Social is celebrating goaltending with NHL Goalie Week from Aug. 26 to Sept. 1, reveling in the uniqueness and artistry of the puck-stoppers through the decades. In that spirit, NHL.com columnist Dave Stubbs takes a look at late Montreal Canadiens legend Bill Durnan, statistically the greatest at his position during the 1940s. Sixty years ago on Aug. 29, Durnan was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame as a member of the Class of 1964.

The numbers of the late Bill Durnan are practically off the charts.

Fifteen strikeouts per game for 25 consecutive years on a fast-pitch diamond as one of Canada’s finest softball pitchers ever. Fourteen no-hitters, officially, but surely many more than that. Two world championship victories playing on teams out of Toronto, his hometown. Lifetime batting average of .350.

On the soccer pitch, as a young and powerful halfback, Durnan was scouted by two English First Division teams, offered contracts by each.

But since we’re here for Goalie Week, let’s add these statistics from Durnan’s remarkable NHL career of just seven seasons, all with the Montreal Canadiens:

Two Stanley Cup victories, in 1944 and 1946. Four-time NHL leader in wins. Six Vezina Trophy wins for the League’s lowest goals-against average between 1944-50. His run was interrupted only by the Vezina win of Turk Broda, the five-time Stanley Cup champion for the Toronto Maple Leafs, who was stingiest in 1947-48.

Durnan died at age 56 on Oct. 31, 1972. He had been admitted to Toronto’s North York General Hospital a week earlier, the day before he was to serve as a pallbearer for Broda, his dear friend and goaltending lodge brother, who had died on Oct. 17 at age 58.

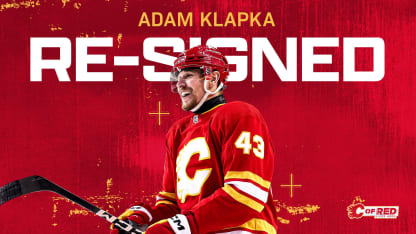

With fellow players Doug Bentley, Albert “Babe” Siebert and John “Black Jack” Stewart, Durnan was a member of Hockey Hall of Fame’s Class of 1964, induction ceremonies held 60 years ago on Aug. 29.

Happy-go-lucky, his nerves finally shot from the strain of playing in hockey-mad Montreal, Durnan retired in 1950 while still playing superb goal. He yielded the Canadiens net to Gerry McNeil, the under-appreciated 1953 Stanley Cup champion who bridged the position between Durnan and trailblazer Jacques Plante.

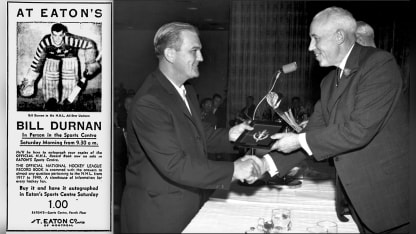

© Montreal Gazette; Hockey Hall of Fame

Bill Durnan in a Jan. 21, 1950, newspaper ad for his Saturday morning autograph appearance that day at Montreal’s Eaton’s department store. Durnan met fans for two hours, defeated the Boston Bruins that night on home ice, then travelled to Boston overnight by train to beat the Bruins again the next night, on his 34th birthday. At right, Durnan accepts his Hockey Hall of Fame plaque from NHL President Clarence Campbell on Aug. 29, 1964.

Durnan ended his career with 383 regular-season games played between 1943-50, his record 208-112 with 62 ties, a goals-against average of 2.36 and 34 shutouts, 18 of them coming in his last two seasons. With shots on goal only sketchily kept, no official save percentage was recorded.

In the playoffs, Durnan was 27-18 in his 45 games between 1944-50 with a 2.07 average and two shutouts.

He strung together 309 minutes and 21 seconds of shutout goaltending, which ranks fifth all time in the NHL, during the penultimate year of his career.

His salary having topped out at $10,500, Durnan was among the 100 Greatest NHL Players named for the League’s 2017 Centennial year, and an arena bears his name in Montreal’s Cote-des-Neiges/Notre-Dame-de-Grace district — on rue Vezina, no less.

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

Bill Durnan as a member of the Kirkland Lake Blue Devils, that team winner of the 1940 national senior championship Allan Cup; and posing at Maple Leaf Gardens with Canadiens legend Maurice “Rocket” Richard during the 1940s.

The six-foot, 190-pound three-time All-Star was renowned for his ambidextrous style in goal, wearing two primitive leather trapper/blockers to switch playing from left to right as the play dictated. He didn’t wear just one fastball-polished glove, he wore two.

Canadiens coach Dick Irvin Sr. thought so highly of Durnan’s leadership that he put the captain’s “C” on his wool sweater for the latter half of the 1947-48 season upon the career-ending injury suffered by Toe Blake, the future coaching legend who, during part of the 1940s, had played left wing on Montreal’s iconic “Punch Line” with center Elmer Lach and right-wing Maurice “Rocket” Richard.

Durnan was the sixth and final goalie to serve officially as the on-ice captain of an NHL team.

The NHL decreed in its 1948-49 rules, a regulation that remains in force, that “No goalkeeper shall be entitled to exercise the privileges of Captain or Alternate Captain on the ice.”

“Irvin gave me a little more responsibility than most goaltenders by naming me captain,” Durnan said, quoted in hockey historian Stan Fischler’s 1994 book “Heroes and History.”

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

From left: Canadiens Floyd Curry, Bill Durnan (wearing the captain’s “C”), and Kenny Reardon in action at Maple Leaf Gardens during the 1947-48 season.

“In those days, a captain could complain more to referees than now. One of my duties was to report back to the coach as to what was happening on the ice when something went wrong.

“Well, I looked a little stupid if there was a bad call against us — me with all those pads and the big stick, chasing after the referee and then running to the bench to hear Irvin.

“I used to have a few run-ins with ref Bill Chadwick, but he had a knack of saying, ‘Hey, Bill, where are you going to eat after the game?’ whenever I’d reacted my most heatedly. That would completely distract me and I’d wind up flabbergasted.”

© James Rice, courtesy Montreal Canadiens; Dave Sandford/Hockey Hall of Fame

Bill Durnan poses for a 1940s Montreal Canadiens studio portrait. The future Hall of Fame goalie wore this belly pad/chest protector near the end of his seven-season NHL career.

Durnan was the first rookie in NHL history to win the Vezina Trophy, joining the Canadiens in 1943 at age 27. It wasn’t an easy debut, fickle Montreal fans chanting on a shaky night for the return of popular journeyman Paul Bibeault, the goalie he had replaced. But with his sprawling, flashy style and easy-going manner, he quickly played his way into the city’s heart.

Durnan had first attracted attention with his 1930s exploits in Toronto and Sudbury junior and senior goal.

The Maple Leafs had great interest in him until he twisted his knee in 1932, then they looked away. Undeterred, Durnan played on, ultimately leading the 1940 Kirkland Lake Blue Devils to the country’s Allan Cup senior hockey title.

He would continue to grow with the senior Montreal Royals from 1940-43. By now looming larger on the radar of all six NHL teams, Canadiens general manager Tommy Gorman heard coach Dick Irvin’s pleas during 1943 training camp to sign the impressive prospect before someone else did.

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

From left: Montreal Canadiens Maurice Richard, Glen Harmon, goalie Bill Durnan, Leo Lamoureux, Elmer Lach and Toe Blake in a 1940s photo. Richard, Lach and Blake formed the Canadiens’ feared “Punch Line” during this era.

“He’s the best goaler in 20 years in the NHL because he has the most competitive spirit,” Irvin would say. “He’s the least temperamental and he’s the greatest of all goalers under fire.”

Durnan wasn’t an easy sell, making a decent dollar in senior without the pressure of NHL goaltending.

Ten minutes before the Canadiens’ first game of the 1943-44 season, the tight-fisted Gorman still didn’t have Durnan’s name on a contract. So the GM finally offered a sum that the goalie liked and Durnan signed, racing into the Montreal Forum dressing room, suiting up and playing impressively in a 2-2, career-opening tie against the Boston Bruins without so much as a warmup.

Like his brethren in the one-goalie days of the NHL’s so-called Original Six era, Durnan was a warhorse and a warrior, playing hurt and with injuries not disclosed to management, lest the team bring in another man who might take his job.

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame; Graphic Artists/Hockey Hall of Fame

From left: Canadiens Kenny Reardon, Bill Durnan and Butch Bouchard during the late 1940s at Maple Leaf Gardens; and Durnan (right) presenting Canadiens goalie Charlie Hodge with the 1963-64 Vezina Trophy at the NHL’s All-Star banquet at Toronto’s Royal York Hotel on Oct. 9, 1964.

Montreal Star hockey writer Red Fisher remembered Durnan upon his death in 1972, recalling a moment near the end of the goalie’s career.

“Durnan was badly slashed around the head, cut by somebody’s skate,” Fisher wrote. “The game was in Chicago and Bill was brought home to Montreal for hospital treatment. I met him at the train station and rode with him to the hospital in an ambulance.

“He said, ‘That’s it, I don’t want any more of this. I’ve had enough.’ He came back to play again, but not for long. Eventually, the game became too much for him. He was probably at his greatest under pressure, but the pressure finally was too much.”

Former teammate Toe Blake mourned the loss of a friend and a great leader, a fellow legend who wore the Canadiens captain’s “C” immediately following himself.

© Turofsky/Hockey Hall of Fame

Bill Durnan dives across the goal crease for a 1940s publicity photo taken at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto.

“Nobody knew he was that sick, but you know Bill,” Blake said. “When I was in Toronto in August for Hall of Fame ceremonies, I talked to Mandy (Durnan’s wife) and she said, ‘He won’t go to the doctor. He won’t go to the hospital. He had a knee injury for years, cartilage trouble. He should have an operation when he was playing junior, but he didn’t do anything about it.’ ”

After retirement, Durnan coached junior and senior hockey and dabbled in various business ventures.

“All of us looked up to Bill,” Blake said of his Canadiens teammates. “We looked up to him as a man. Some of us on the team, me and Murph (Chamberlain), we were older than Bill but we looked up to him.

“At his best, nobody was as good. Nobody. He was a great athlete.”

Top photo: Bill Durnan lunges for a puck in this 1940s publicity photo taken at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto.