White-Knuckle Ride: What’s it like watching white-collar boxing?

By Elliot Worsell

AS a chipper, ponytailed Asian woman in a blue headguard shimmied down the runway, half a dozen sozzled but smartly dressed blokes sitting at a table waited for the drop in her ring entrance song – ‘Don’t Wanna Know’ by Di & Shy FX & T Power Feat. Skibadee – and used it, this cue, to transport themselves to the nightclub, bouncing first with each other and then with her.

They had no idea who she was. They were waiting to see someone else. But still these men jumped around and fist-bumped shiny new boxing gloves; still they, and 1,600 others, made this girl with the popular walkout tune, this girl more Pokémon than pugilist, feel special on the night she played dress-up and boxed for the very first time.

“Is this the first time there has been a feature on white-collar boxing in Boxing News?” asked Jon Leonard, the founder of Ultra White Collar Boxing (UWCB), an hour into his company’s latest Saturday night show at Stepney’s Troxy. Informed that was indeed the case, he then wondered, “Why now?”

Two weeks earlier I listened to another white-collar boxing exponent ask a similar two-parter. Unlike Derby-based Leonard, however, this promoter treated my introductory call with a far greater degree of scepticism. “We know the pro boxing lot don’t like it,” he said. “They never will.”

Regardless, he agreed to be interviewed later that day and would, he promised, put all concerns about quality and safety, the presumed reason for the call, to bed. But, of course, when “later” arrived, he was again busy. Double busy. Busier still the next day. Finally, by the end of the week, calls were ignored altogether, and he resorted to hitting the block button.

As an introduction to the world of white-collar boxing, it was hardly encouraging. Right or wrong, it suggested there was fear among those making money from ill-equipped novices getting in the ring and that if people started looking too deeply into it – into its practices and motives – there might be cause for concern. He wasn’t just difficult or evasive, this promoter. He didn’t simply no-comment his way out of a tricky interrogation. No, he ducked and dived. He eventually fled. From the outset, he gave the thing a bad name.

Suffice to say, then, the welcome extended to BN at the aforementioned Ultra White Collar Boxing show on December 15 was both refreshing and much needed. Warm and sincere, it indicated the savvier Leonard and his company viewed the sudden interest in their product not as a cause for concern but instead, and rightly, a watershed moment for the white-collar boxing movement and a sign they were doing something right.

If Leonard was the headmaster, and Ultra White Collar Boxing was his school, BN represented Ofsted. We went in with eyes wide open, we hoped to be impressed, and we too wanted to know the answer to Leonard’s question: “Why now?”

Chances are, a bit like a marathon, we all know someone who has either had a white-collar boxing match, contemplated doing one, or revealed it is something they intend to eventually check off their bucket list. For those unaware, or those mulling it over, the process will typically go a little something like this: a participant signs up to an eight-week training camp overseen by experienced coaches, and during these two months they get fit, learn how to box, and raise money for charity. This then culminates in a single boxing match, fought over three two-minute rounds, against another member of their gym with whom they are evenly matched. So far, so simple.

“From a participant’s point of view, there’s no cost at all,” Leonard explained. “They sign up, the training is free, we get their vests printed for them, and we pay for the trophies and insurance. We expect them to sell some tickets, which pays for everything and is how we make money, and we expect everyone to raise money for Cancer Research UK.”

UWCB, like any business, will lose money on some events, but the overall model seems an effective one – they “destroy” the take-home money of most lower-level pro boxing promoters, I am told by a lower-level pro boxing promoter – and participation levels are going up and up, seemingly in correlation with the growing popularity of the pro game. Saturday’s show at the Troxy, for example, was just one of 20 UWCB were hosting that night alone. “From Inverness to Southampton,” Leonard said, before explaining that since 2009, the year UWCB ran its first event at Syn nightclub in Derby, they have seen over 50,000 people take part.

For some, a white-collar boxing experience will have altered their opinion of a sport they would otherwise have avoided had it not been packaged as accessible – something for everyone – by a company like UWCB. What’s more, many of the participants who once had zero interest in boxing will now, thanks to their white-collar moment, represent a portion of the so-called ‘casual fans’ who buy tickets to professional shows and purchase pay-per-view events on television.

“We get people who walk into a boxing club for the first time and think they’re going to get attacked,” said Leonard. “But they walk in and the trainers are like, ‘All right, how are you doing?’ Everyone’s nice and welcoming and helpful. The good thing about this is it’s exposing the public to that. I think we’ve let Joe Public see what boxing’s all about.

“A lot of participants add me on Facebook and I see, within three months, their timelines go from featuring nothing about boxing to seeing pictures of them flying to Germany to watch Wladimir Klitschko. They’re suddenly buying tickets and pay-per-views.”

Best of all, since they started raising money for Cancer Research UK in 2013, the boxing branch of Leonard’s company, which hosts 400 shows a year, has generated £14 million, while Ultra Events, as a whole, have hit £16.2 million. “Everything about it is positive,” Leonard will repeat, proudly, loudly, and it’s hard to argue. The atmosphere is positive, the attitude of the one-night-only combatants is positive, and the reasons for its existence are not only positive but admirable.

However, just as the perks of pro boxing can be undone by an isolated incident which serves to highlight its inherent dangers, so the good work of its white-collar counterpart can be undermined by sporadic moments of darkness. In 2017, for example, Ben Sandiford, a 20-year-old engineer, was reported to have been left fighting for his life after he suffered a bleed on the brain and two heart attacks following a white-collar bout in Crewe. Rushed to hospital, he had a seizure, two cardiac arrests and ended up on a ventilator in a critical care unit. He was kept in for 17 days and his family called for white-collar boxing to be banned.

Months later, in August, Adam Smith, a 34-year-old boxing novice from Eastleigh, discovered the requisite eight weeks of training wasn’t enough to stop him losing on points to an opponent who later told him, according to the Daily Mirror, he had been doing mixed martial arts training for seven or eight years.

But, worse than that, some 19 days after the bout, Smith, complaining of headaches, collapsed at home with a stroke, and suffered a second one the following day. Upon being taken to hospital, doctors found a ruptured artery in Smith’s neck – deemed a boxing injury – and he underwent an emergency operation to save his life. He only wanted to get fit and do something charitable but was left temporarily paralysed and without vision on his right side.

Ultra White Collar Boxing, the leaders in their field, refused to accept the accusation Smith was overmatched, and stressed the two boxers had been put together following eight weeks of training and assessment. A spokesperson said: “This bout was fairly matched within UWCB’s matching guidelines. They were both of similar ability and fitness and both weighed 100 kilograms. During our investigation, we have confirmed it was a fair bout.

“All participants receive a pre-bout briefing from the medics during which they are given advice on head injuries. In addition to this, participants are given verbal advice on injuries as well as being handed a head injury card following their bout.

“After the bout, both competitors posted on Facebook stating that they enjoyed their experience and thanked UWCB for the experience.”

As for Sandiford, he was apparently “alert and thinking clearly” during an assessment by medics and suffering “no signs of neurological deficit, so his condition was not classed as an emergency”. Leonard said the family wanted to make their own way to hospital as he was standing outside “getting some fresh air” and stated: “He had no pain anywhere.”

Had either of these incidents happened on a pro boxing show, there would still have been calls for the art of punching people to be scrubbed from a now apparently civilised society. But because they took place on a white-collar boxing show, this five-a-side football equivalent of the pro game, the target was so much larger and so much easier to locate. It wasn’t professional, the abolitionists screamed. It was Fight Club for real – not a book, not a film, not something one should be doing for fun.

With criticism coming from all angles, England Boxing, who oversee Olympic-style amateur boxing, raised concerns about safety standards at white-collar bouts, and said: “The lack of a recognised governing body for white collar boxing means the sport is effectively unlicensed with no harmonisation of rules and regulations. This leads to alarming variations in safety standards at white-collar shows which pose a significant threat to the health of the boxers.”

Therein lies the problem. On the one hand, increasing levels of participation helps to promote boxing and raise millions for charity, yet, on the other, a rise in participation will also invariably lead to countless cowboy companies attempting to cash in on the white-collar revolution, thus diluting the product and its safety standards, and blackening its reputation.

Then again, even when it’s done right, and nobody, I’m assured, does it better than Ultra White Collar Boxing, it can still go wrong. It’s boxing, after all.

“It’s always going to happen when punches are hitting heads, but it’s about making it as safe as possible,” said Brian Magee, the former WBA super-middleweight champion whose company All Star White Collar Boxing has this year raised £50,000 for Action Cancer. “I have an ambulance crew, two ambulances waiting, and there’s a lot of money invested in the night. You might go to some other event, though, and there will be none of that in place because they’ve cut back to save money. Some are just about making money.

“This means if you’re the last person in the group to get matched, you’re fighting him or her no matter what. What I do, if it’s not a fair fight, is say, ‘You can get your training done, but you won’t be guaranteed a fight at the end of it.’ It’s all about matching abilities. If you’re happy with the match, and the boxers are happy, it all goes ahead. If it doesn’t happen, you wait and move on to the next event to find a more suitable opponent. There’s no pressure on them.

“Elsewhere, people get thrown into fights they don’t want to take and come back complaining that they were overmatched. They’ll come away from that experience with a bad feeling about boxing. That’s the one thing I’m trying to change with the white-collar boxing. I want boxing, as a sport, to come out with its reputation enhanced.”

Magee, as a former pro fighter, is blessed with an ability to not only pass on advice to those on his training courses but to also spot the hustlers among them; the ones who ease off in training in the hope of being matched against a weaker opponent on fight night. It’s an intuition he believes others involved in the white-collar scene might lack.

“That’s the one thing I’m against: people with no boxing experience running the events and doing the training as well,” he said. “There are people over here who have maybe done one white-collar event and are now calling themselves boxers and working with other people. But there’s no better teacher than an actual professional boxer. That’s especially true during the training part because the training is the most important and dangerous part.

“We train everybody for four weeks before they even put on a glove. But there are other guys I know who let people spar in their first week. At that point they have no idea how to defend themselves or even throw punches. It’s just bad from the start.

“Some of these people are basically coming straight from the pub following years of drinking and suddenly thinking they’re going to be boxers. You must have a certain base of conditioning, though. That’s why we start with four weeks of proper conditioning and training. We ease them in gradually.”

Wayne Alexander, a former British and European super-welterweight champion, was one of three referees at the Troxy on December 15 and has found a second career officiating white-collar shows up and down the country. He, more than anyone, is privy to the fair fight and mismatch ratio.

“The majority of the time, especially with Ultra White Collar Boxing, it’s fairly matched,” he said. “On other shows you do get the odd one where you see a guy has probably boxed before and that happens because there are no official records. Somebody could have boxed 10 years ago and had 20 fights and then they go and do a white-collar fight. They might only have had 20 novice fights, but he still boxed and knows what he’s doing.

“That’s dangerous in the white-collar scene because you don’t get brain scans or blood tests. So maybe there are guys involved who shouldn’t really be involved.

“The safety probably isn’t as great as a British Boxing Board of Control-regulated show, but the Board have the financial backing, don’t they? Also, some promoters will only promote a show once a year. For some of them it’s just a hobby thing.”

On the subject of brain scans, Leonard said: “We have looked into this and been advised by the medics who help us carry out risk assessments that, due to radiation levels in CT (computed tomography) scans, it would do more harm than good to scan 15,000 people every year.

“England Boxing do not have brain scans and we are in line with their procedures. We did research mobile brain scanners for post-bout medicals, but they were deemed not reliable by our medical suppliers.”

“A lot of people just want to box once to say they had a go, and you can’t expect them to spend hundreds of pounds on medicals,” Alexander added. “But you don’t play boxing.”

Though now a cliché, this closing line is a pertinent one in the case of white-collar boxing. For while a few games at the local tennis club might follow Wimbledon dominating our television screens, or an encouraging but ultimately disappointing World Cup run for England might lead to a surge in five-a-side football participation, the increase in boxing’s popularity seems to have resulted in men and women exploring the virtues of an eight-week training camp and a three-round fight. That’s all well and good, of course, but whereas most of us are able, or at least safe, to hit or kick a ball, far fewer are equipped to give and take punches.

“When you do the marathon, you sign up online, you pay, you’re posted a vest, you turn up on the day, you go for a run, and someone gives you a medal and you go home,” said Leonard, who formerly worked as a warm-up coach at Race for Life events across the Midlands. “After crossing the finish line at the London Marathon someone gave me a chocolate bar and a medal. That was it. I had to lie down on the carpark floor for 20 minutes before we drove home. I was done in.

“When you think about it, rugby players turn up, put their kit on, have a rugby match, get hit around the head, go to the pub, and then sink 16 pints. How is that safe? With fight sports, we’re forever doing risk assessments and considering risk. As long as that pre- and post-fight care is there, we’re making it safe considering people are punching each other.”

Long before spotting the bars or DJ booth, the first thing one would have noticed at the Troxy that Saturday was a stretcher by a wall and paramedics dotted around ringside. It wasn’t for decorative purposes, either. All UWCB events, in fact, have three waiting ambulances, an HCPC (Health and Care Professions Council) registered paramedic, as well as two Emergency Medical Care Assistants who have a frontline A&E ambulance with life-saving equipment, including a full drug kit. (Of the three medics, two are permanently at ringside, while the third carries out the post-bout medical checks.)

On one of the ringside tables, meanwhile, Leonard manned an event health and safety pack and was accountable for signing off the construction of the boxing ring and the medics arriving on site. When they showed up, they were asked to provide their HCPC card, which proves they are registered, and this was then matched with their photo ID and checked on a computer to ensure it was valid. “We basically check they are who they say they are and that they are properly qualified medics,” Leonard said.

After that, the medics, as well as the corner personnel and security, signed forms claiming responsibility for their role in the event. This supposedly prevents anyone turning up in the wrong frame of mind, perhaps distracted for some reason, and alerts them to the location of the nearest hospital and ringside oxygen supplies. Moreover, there were pre-fight medical reports for all the boxers involved that night and this paperwork would highlight any issue – such as asthma, for instance – and allow a medic to deal with the situation accordingly.

“As soon as a person has boxed, the medics will literally ferry them back to the medical room for their post-fight medicals,” said Leonard. “During the post-fight medicals, the medics read a standard script and give everybody head injury advice.

“I think the reason why boxing is so safe is because of the post-fight care. We’ve been doing post-fight medicals for years but not all boxing events do it. In the amateurs, for example, you don’t have to have a post-fight medical. But it’s something we insist on. It’s part of our paperwork and it’s standard practice.”

The fight night equipment, too, has safety in mind. Supplied by UWCB, to ensure it’s the same for every fight, each boxer wears a headguard and specially-made 16-ounce gloves which have high-density foam packed around the knuckle area. “We don’t let people bring their own kit,” Leonard said. “We supply it. And all this stuff is generic. It’s happening here and it’s happening right now in Inverness and Southampton.”

It was all happening that Saturday night at the Troxy, what with 41 fights split across two rings to get through. Dhol drummers took to the walkway at 4.30 pm, the master of ceremonies called the boxers to the two rings, Rihanna sang about finding love in a hopeless place, and the boxers, all of whom wore either red or blue vests on which their name, nickname and occasionally a sponsor’s logo were printed, disguised nerves with dance moves, selfies and waves to the crowd.

The crowd, for their part, tried to spot their boxer, their primary reason for coming, but were also encouraged to cheer for either the red or the blue team; a smart atmosphere-building technique which aided noise levels throughout the night. It felt, for a moment, like being transported back to Saturday teatime in the nineties. Contenders ready. Gladiators ready.

“We very much try and work on getting the crowd to support either the reds or the blues,” Leonard explained. “There are 1,600 people in here today, but one boxer may only have sold 20 tickets. If only 20 people cheer for him, there won’t be much of a noise. We really work to try and get the whole crowd behind all of the boxers.”

There are many things pro boxing promoters could learn from an Ultra White Collar Boxing promotion, and the emphasis placed on selling the event, as opposed to a single fight or fighter, is just one of them. The buzz is consistent as a result, even when the action inevitably dips, and seats remain occupied due to the fact the night’s running order is kept under wraps until the last minute. This guarantees a full house for pretty much the duration and eradicates the prospect of people exiting the building upon seeing their point of interest box, as is often the case in pro boxing (when a running order is revealed days in advance).

“The first fight has to have an amazing atmosphere,” said Leonard, “and then that atmosphere stays for the night. It’s fair on everyone to have that banging atmosphere. You wouldn’t want to go on first and box in front of 50 people because the rest are turning up late.”

The experience is all the better for it. There are bums on seats and food and drink in hands. Even the attire of the punters separates it from your usual boxing fare. A strict smart dress code is imposed and the reason for this, more than simply deterring ruffians in jeans, owes to Leonard’s belief that getting dressed up would act as a stronger incentive for couples or groups of friends to stick around and make a night of it. He called enforcing it “torturous” at first, but it seems to have now worked.

In Belfast, meanwhile, Brian Magee goes for something a little different but leans similarly on glitz and glamour.

“I do a Vegas-style set-up,” he said. “I put on no more than 10 fights and the boxers do three one-and-a-half-minute rounds. It’s almost like an amateur bill. I’ll do five fights and then have some halftime entertainment. That entertainment factor is important to me. A lot of white-collar companies just think, ‘Great, we’ve got 40 fights, happy days, we’re making a fortune. Let’s just have people fighting all night long.’ But that puts me right off.”

Before the boxing at the Troxy got underway, one man, Vikesh Tailor, was singled out to receive a special medal from the master of ceremonies. It was his reward for being the event’s top fundraiser, a position he achieved by generating £2,585 of the £36,195 raised that night for Cancer Research UK. It was a heart-warming moment. A nice touch. Yet, without wishing to rain on Vikesh’s parade, a woman on the last Derby show – female participation on UWCB shows this year rose to 30% – somehow raised a staggering £21,000 on her own (a feat all the more stunning given £286 is the average amount raised per participant).

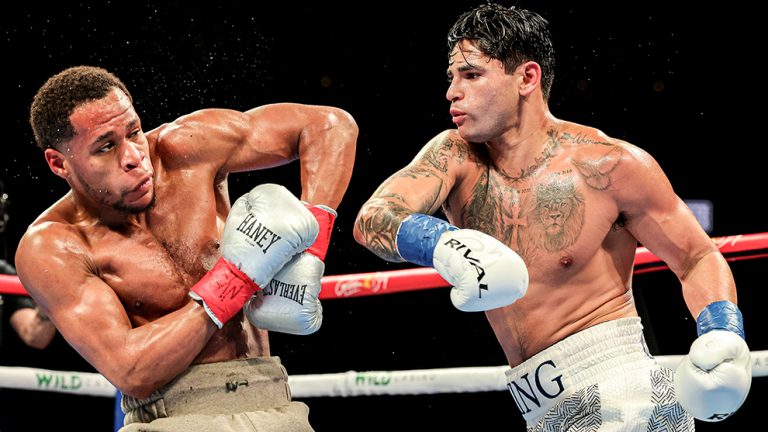

“Let the brawling begin!” roared the MC and brawling was the most appropriate way of describing what would soon unfold. Fights one and two at the Troxy were strangely watchable, with punches surprisingly straight, yet these proved exceptions to the rule when the next two featured free-swinging novices spinning around, shirking conflict, and occasionally scurrying away. Though expected, it was, at times, difficult to watch. “Stop the fight, referee!” said one punter behind me, so tired was he of seeing a man, his hands by his knees, unable to face his opponent. “What’s the point?”

Unbeknown to this peacemaker, there was a woman in the other ring, ring two, whose eyes were almost always closed and who seemed to hate every second of the experience, the aim of which was to seemingly just reach the final bell (which, thanks to the matchmaking, she did). It’s all in the matchmaking, Leonard was quick to remind me.

“They all start training together but won’t get matched until a week before the show,” he said. “Some will train every day; some will train twice a week. I know some people running white-collar shows match them up at the start, which, to me, is mad. You don’t know where someone will be in eight weeks. They’ll be weighed a few times during the process and four or five days before the fight they’ll find out who they’re fighting.”

By bouts three and four audience members had forgotten all about their loved-one’s place in the running order, much less the finer points of technique, and were cheering only for colours, cool entrance songs, unsightly pirouettes or the ring card girls and ring card boy. Yes, ring card boy; a ring card boy whose beaming smile was reciprocated by everyone in the venue.

“With some of the fights you think the guys have literally come out of a pub and been given gloves,” said Alexander. “But I have seen, on the flipside, guys who have made me say, ‘Bloody hell, these guys are ABA-level.’ I’ve even said to a few after they’ve boxed, ‘Why don’t you do ABA?’ They might say they’re too old or not that dedicated, but there are some talented guys out there. I’ve seen all kinds in white-collar.”

Which brings us to Omari Grant. In 2015, Grant boxed on an Ultra White Collar Boxing show, having never before shown an interest in the sport, and did so to support a friend. He impressed during the eight weeks of training, won his fight, and then later used the experience as the launchpad to a professional boxing career. He is now 8-0 as a pro.

“I proved something to myself just going through with that white-collar fight,” he recalled. “A lot of people were telling me not to do it. They were talking about the dangers.

“I was getting a lot of negative feedback from people who didn’t really know much about boxing. They didn’t know how I was going to be able to learn boxing in such a short time. Would I be able to protect myself? All those things were relevant in my case.

“In the end, I found out I’m mentally stronger than I thought I’d be in that situation and it was a catalyst for me to go on to bigger things. Personally, that was the best thing I could have done.”

Later, Grant accepted an unlicensed fight at two weeks’ notice. He lost against an ex-professional, but the competitive nature of the bout, as well as the fact he had very little time to prepare, gave the 30-year-old the impetus to apply for a pro licence.

“I would always encourage people to go down the amateur route,” he said. “That’s the best way to learn your basic skills and prepare yourself for a proper fight.

“Also, I think there’s more danger in the unlicensed circuit. There are no headguards, the gloves are lighter, and it’s a bit more serious. With white-collar, you have the headguards, the big gloves, and everybody is a novice.

“It’s only when they’re putting people in who aren’t novices, who really want to win, who aren’t doing it for a good cause, that there’s trouble. If you had unlicensed guys moving into white collar, that would be a problem. But I think they screen that and match guys accordingly.

“Basically, if you want to do white-collar for the experience, and for a good cause, and you have the heart to do it, I’d definitely encourage it. It ignited something in me I didn’t think I had.”

By Leonard’s estimation, Ultra White Collar Boxing has now been responsible for 10 boxers with pro licences. “For people in their mid-twenties to go from having never boxed to being a pro boxer is mind-blowing,” he said. “One day a kid will go to the Olympics and they will be going because their mum or dad once took part in this. That will be incredible.”

It will, no question. But, equally, it could be said the real poster boys and girls of white-collar boxing are the following: the insecure lad in Derby who turned up nervous and fearful on day one of training, lost his fight, but discovered something about himself in the process and signed up to do it all over again with a different frame of mind; the obese man in Bradford who has now lost 12 stone and completed the London marathon since using a white-collar boxing match to kickstart the life change; the Asian girl in London with the show-stealing ringwalk song who reconnected with her opponent at the Troxy bar moments after they had been punching each other in the face.

Ultimately, boxing will always have a proclivity to supply its own black eyes, such is the nature of the beast. It will always self-harm. It will always polarise. It will always, to some, be just punching.

Yet, considering white-collar boxing is geared towards funding charities rather than egomaniacs or promoters, and is a watered-down product designed to entice rather than dupe the masses, it is difficult, when done correctly, to see too much wrong with it. It will never be whiter than white, no, but let’s not kid ourselves, neither will boxing.