The Man in the Middle: Roberto Diaz on the art of matchmaking

ROBERTO Diaz left Golden Boy Promotions having, as one of the world’s leading matchmakers, long been so crucial to their success. During a potentially defining time in their short promotional history, his influence can perhaps even still be felt. By Declan Warrington.

The fight between Saul “Canelo” Alvarez and John Ryder, in Guadalajara on Cinco de Mayo weekend last year, came weeks after Roberto Diaz had suffered a heart attack, and yet the respected matchmaker was ringside – watching, and absorbing – having travelled from Los Angeles to be present.

He was joined there his wife Carla, who has long worked for the world’s leading fighter. Weeks later he then watched from afar when Jaime Munguia narrowly outpointed Sergiy Derevyanchenko and with particular interest, given he had also contributed so much to Munguia’s career before Diaz’s departure from Golden Boy Promotions earlier in 2023.

Throughout his 15 years with Golden Boy, he had come to be recognised as one of the world’s finest matchmakers, and an essential figure at a promotional organisation that for a period was widely considered the most powerful in the world. Ryan Garcia’s recent victory over Devin Haney has strengthened their interests even more than perhaps would Munguia defeating Alvarez or Vergil Ortiz Jnr beating Tim Tszyu, but even then they may not again rediscover the heights reached previously, when the super fights and the presence of Oscar De La Hoya, Bernard Hopkins, Shane Mosley, Ricky Hatton and more gave them such appeal.

It was Diaz, through his long-term association with Marco Antonio Barrera, who before joining Golden Boy had put Hatton in contact with De La Hoya and De La Hoya’s then-partner Richard Schaefer, ensuring that the fight between Hatton and Floyd Mayweather was made. Mayweather, by then, had already defeated De La Hoya on another Golden Boy promotion; the two biggest fights of 2007 were ultimately theirs.

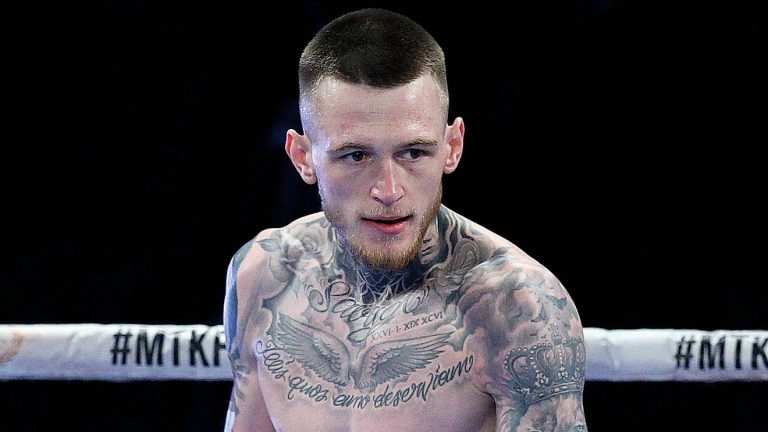

A-list association: Marco Antonio Barrera (Stephanie Trapp/TGB)

If it was also through Barrera that Golden Boy and other fighters first became aware of Diaz, it is since his separation from the Mexican that his reputation has grown. Like Barrera – and indeed De La Hoya, Hopkins and Schaefer – he may never again be quite so influential, but like so many others who worked alongside or against him, he will forever know how responsible he was for so many fine fights being made.

To learn the full picture of Diaz’s 55 years is to learn of a lifetime before his meeting with Barrera. Of the trappings of gang culture in San Francisco, where he was born, and his father forcing him to relocate to the Yucatan region of Mexico where it was beyond him; of his occupations as a salesman and as a parole officer; of the life-threatening car crash and successful battle against cancer that saved his marriage on account of the commitment Carla continued to show him when they had previously decided that they should divorce.

It is perhaps for those reasons that the perspective Diaz has gained – his most recent health scare followed his departure from Golden Boy – is even more acute. By his own admission there were times his family was neglected while he pursued what he describes as his “dream”. Perhaps the demands of his profession and the rate at which Golden Boy was growing even means that was the only way that it could ever have been.

“That’s what I learned after the 15 years when we parted ways,” he tells Boxing News from his home in LA. “Another message is first is your health; second is your family, and third is your job, because your job’s always going to be there as long as they need you. Family has to be there.

“I don’t want to sound like I regret it, because it got me to where I am and who I am today, but you gotta give your family that importance, and there were times – ‘I’m sorry; I can’t make it to that’ – because work comes first. There was a [Barrera] fight. I was in camp. My father [Roberto] had been sick for 30 years. They depend on me – I gotta be here.’ ‘Man, I should be going – when the fight’s over I’m gonna head out.’ He passed away the morning of the fight. One more day, I probably would have saw him. Marco – his whole family – everybody knew. Marco gets cut, so after the fight I rush him to get stitched up. We get back to the hotel. The pool’s reserved for an afterparty. Everybody’s with this long face. I turn around, and Carla’s sobbing. ‘My dad died, huh?’ In retrospect, the job was always first.”

Barrera’s faith in Diaz – first following their meeting at a shopping centre in San Diego, where Diaz then lived, then when he fought Cesar Najera in Fantasy Springs – led to an invite to join his training camp in Big Bear, California, for his unforgettable first fight with Erik Morales. The commitment Diaz showed contributed to him later being so instrumental towards the timing of the third fight of their trilogy – Barrera secured his second victory over his greatest rival – Diaz’s reputation growing, and eventually the offer to be the assistant matchmaker to Eric Gomez.

“In probation I worked a week and rested a week, so I’d go up for a couple of days and spend it in camp; run with them; eat with them,” he recalls. “Eventually, from being a fan; a friend, says, ‘Why don’t you go in with the flag for my next fight?’. They went on to have an amazing trilogy.

“‘I’m gonna sign with Oscar De La Hoya; Golden Boy Promotions.’ Golden Boy was just starting; [outside of De La Hoya] Marco was their biggest name. ‘We’ve got our first fight, against Manny Pacquiao.’ We’re in Big Bear, and what I saw was a fast, young fighter that had a lot of trouble with the jab. Marco had a beautiful jab – a power jab, because he’s a southpaw converted. ‘I don’t see anything better than Naseem Hamed. Naseem was more awkward; punched harder.’ Fast forward, a hall-of-fame, tremendous fighter – amazing fighter – and something that comes around once every 100 years. But at the time he didn’t seem anything special.

“He loses this fight, and I’m thinking ‘It’s over’. Oscar didn’t cut him; Golden Boy didn’t cut him. Brings him back. From that point on, it was me. I saw Erik Morales have two of his toughest fights the following year and I say, ‘Marco, you need to fight the third fight now’. I didn’t doubt myself in that fight. That win basically put Golden Boy on the map.

“Stepping back, the majority of the fans will tell you [Juan Manuel] Marquez was number one, they’ll probably say Barrera, because he beat Morales twice, was number two, and Morales was number three. Even though the results speak for themselves, I would really almost say Morales was number one, Marco number two, and Marquez number three.

“Remember, I’m with Marco. ‘Let’s call it a day.’ He’s a partner at Golden Boy. ‘Let’s focus on the promotion and the young kids.’ He had other plans [he again fought, and lost to, Pacquiao in 2007]. That’s a fighter always being who they are.”

There started the even-more-transformative decade and a half with Golden Boy – and the evolution of the promoter’s reputation from one that worked with proven champions to one who guided them from the start. Diaz relocated to LA from Sacramento, where his family remained, to accept the offer of working with Gomez, but he considered quitting after each of the first two promotions he oversaw.

“Oh my god,” he says. “They expanded; from one day to the next, and that’s why it was like a crash course. You’re gonna sink or swim. Bernard Hopkins beating [Kelly] Pavlik; it was an amazing time. Everybody wanted to be with Golden Boy. There was a knock on Golden Boy before I got there that if you were a star, already made, that’s where you would go. ‘But don’t go as a young fighter, because they don’t know how to build fighters.’ They had Mosley; Hopkins; Marquez; Barrera; established fighters, maybe close to retirement, but had never produced a world champion. That knock, a few years later with enough time and growth, was gone, because of Abner Mares; [Daniel] Ponce de Leon; Danny Garcia; Adrien Broner; Deontay Wilder; [Jermell] Charlo. That knock quickly went away. I take a lot of pride in it, because I started the careers of a lot of them. I did almost 99 per cent of Wilder’s fights.

“Don’t take it that it was all gravy – I remember a nasty email coming in blaming me for Victor Ortiz’s loss against [Marcos] Maidana. That’s when I learned you gotta have a thick skin. When they win it’s the fighter; the team; the promoter; never the matchmaker. When they lose it’s the matchmaker. It was very intense; fun. But it wasn’t made for the average Joe. There were times there were three shows on the weekend. That’s how busy the time was.

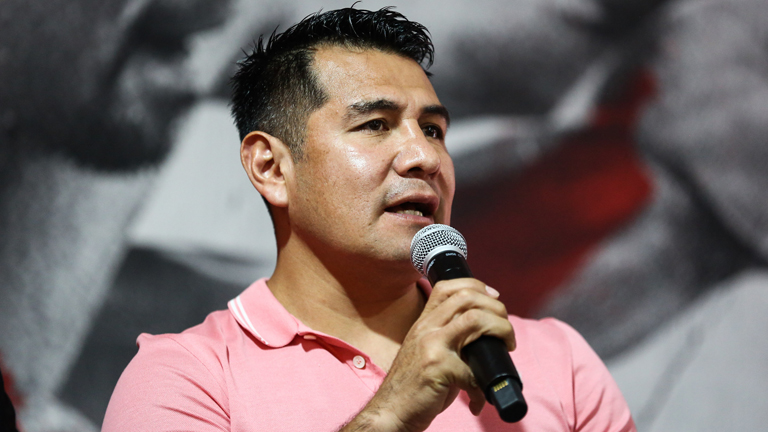

“Richard did a hell of a job. In retrospect I see maybe what Richard saw at the time. Maybe I didn’t see it as clear. ‘Maybe that’s what he saw that he didn’t like.’ But I don’t think Richard and Oscar splitting is why the company changed. The Yankees had an era where they were the number-one team. It’s part of evolution; it’s part of growth. It happens in boxing a lot more.

“There’s no such thing as the perfect show – there’s always going to be something that goes wrong. You’ve gotta go on with the show.”

“Richard [Schaefer] did a hell of a job” says Diaz. (Action Images/Andrew Couldridge)

Through Garcia, and potentially Munguia and [Vergil] Ortiz, Golden Boy are rebuilding. There previously was heartache for Diaz – “The Mayweather loss was devastating, because I really believed [Hatton] would beat Mayweather”; a since healed fallout with Barrera; watching Frankie Gomez’s talent go to waste – and then, even more significantly for he and each of his colleagues, the withdrawal from boxing of HBO.

“When the split [between De La Hoya and Schaefer] happened, it really slows down, because the big name you have is ‘Canelo’,” says the Mexican, whose son Bobby remains with the promoter and also works for DAZN. “He sticks with Golden Boy; all your other fighters are gone. A lot of them weren’t under contract; they leave; along with them leaves networks; Canelo stays; HBO signs Canelo to a long-term deal; that saves us for a time.

“HBO all of a sudden decides to get out of boxing – a huge blow to everybody. Fighters; promoters; boxing in general. You still go back and reminisce and watch some old fights on HBO. They were the best. ‘Okay. What are we gonna do?’ I was a lot to do with the fighters, one-on-one. Not that anyone else wasn’t, but they knew that they could pick up the phone anytime. I wanted to be involved; I wanted to be close to them. You’ve got champions you’re going to have to let go. ‘But you gave me your word.’ I never foresaw Covid and where all this was going.”

Since Alvarez’s departure, Golden Boy have been working with DAZN. Had Diaz not refused to promise Dmitry Bivol a fight with Alvarez, he believes that they would be promoting the Russian, whose potential he identified. Diaz was in Las Vegas to watch Bivol-Alvarez in 2022; when he watches Alvarez-Munguia he will be far from dispassionate; as recently as June 2023 he was responsible for Danielito Zorrilla replacing the injured Liam Paro as the opponent for Regis Prograis.

“Fifteen years,” he says. “It wasn’t easy – people became accustomed to my name getting tagged along with Golden Boy. But my contract ended – every beginning has its end. It was time for both sides to go their way; maybe down the line things will start coming out little by little. How things ended maybe weren’t the best, or at least done the right way. I don’t regret the 15 years – the 14.5 were amazing.

“Only a matchmaker understands the other matchmakers. I want to stay in boxing. That’s my passion. I’m good at it – it’s what I want to do. But in a different role. Let me sit back; advise; do here and there.

“I can see both sides now; it’s not just being a manager that says, ‘You gotta pay more’. I know where the middle is.”