The Beltline: Ben Whittaker and the noble art of disrespect

LAST week a professional boxer accused a commentator of disrespectfully accusing him, the boxer, of disrespect, dressing him down before television cameras in a somewhat disrespectful manner.

Behind them both, meanwhile, was a stage on which a variety of boxers, including Ben Whittaker, the boxer with a bee in his bonnet, had earlier sat. It was on this stage each of them had, to different degrees, expressed their disrespect for an opponent in order to sell a fight. It was also on this stage, during the same press conference, Whittaker had been rudely interrupted; interrupted, that is, by a gatecrasher who approached the top table halfway through Whittaker’s opening comments and disrespectfully called him out while everyone in the room asked the person nearest to them, “With all due respect, what’s this guy’s name?”

Still, Whittaker brushed it off, like punches, with a smile and a shrug. He implored someone in the room to fetch the man who disrespected him, Ezra Arenyeka, a “Sprite and a banana” and then resumed whatever it was he was talking about before being interrupted. In other words, he dealt with the situation properly, maturely. He reacted to disrespect in the best way possible: by ignoring it.

Alas, this would not be the case when Whittaker later encountered Sky Sports commentator Andy Clarke. Standing beside Clarke during a piece for camera, Whittaker was unable to let bygones be bygones and decided to pull Clarke up on some comments Clarke had made in commentary during previous Whittaker fights. It was neither the time nor place for it, but this didn’t matter to Whittaker, whose primary bugbear, it seemed, concerned Clarke’s use of the word “disrespectful” when describing Whittaker’s now-trademark showboating.

Curiously, too, Whittaker’s issue with Clarke appeared to be predicated less on the idea of being deemed disrespectful and more on the idea of his showboating not being considered an artform or a difficult skill. That, if true, would be a strange thing to think, for regardless of your view on showboating there can be no question that such displays of dominance and confidence can only ever be considered acts of utmost difficulty. After all, if such a thing was easy, and if every boxer felt that relaxed and self-assured when in the ring, they would likely all be doing it.

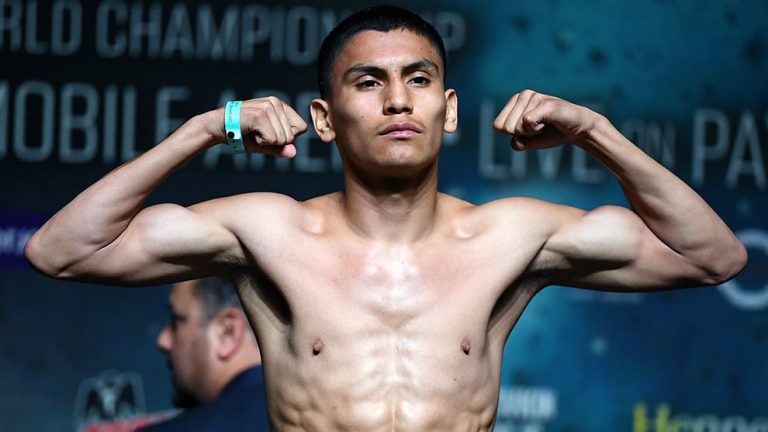

Ben Whittaker ahead of his fight against Jordan Grant (LAWRENCE LUSTIG/BOXXER)

As it is, only Whittaker currently does it to the level at which he does it. It has, to some extent, become his whole personality, in fact, and last week it was difficult to hear his name, either at a press conference or on fight night, and not be reminded that, due only to his showboating, he had become a “viral sensation”.

That’s all well and good, but one wonders whether the people championing him in this way – essentially, reducing him to a Britain’s Got Talent act – are somehow both missing the point and part of the problem. You would hope, given his amateur pedigree and immense talent, Whittaker could be promoted in ways more creative than “viral showboating sensation”, yet to the new faces in the sport, who understand only the language of content and clicks, a boxer’s virality seemingly trumps everything else these days.

As such, Whittaker knows he must play the game. He knows now when to showboat and he knows the kind of moves that will look good when posted as clips on social media. He also argues that this is nothing new to him; certainly nothing fabricated or forced. Instead, and there is evidence of this, Whittaker has included showboating as part of his act for a long time; long before he realised its value and the widespread attention it would bring. In fact, the more you watch Whittaker, the more you come to appreciate that it is an extension of him, almost like a tic, and that to quell this natural behaviour would be to risk reprogramming and malfunctioning the machine. He needs it to punch, basically. He needs it to relax. He needs it to perform.

Ben Whittaker gets down to business against Leon Willings (LAWRENCE LUSTIG/BOXXER)

“We haven’t come to see this,” said Dan Azeez, a current pro, during Whittaker’s most recent win. “We’ve come to see dancing and humiliation. The fans don’t want to watch this.”

Azeez, providing commentary for Sky Sports that night, was sitting alongside Andy Clarke, who, as usual, offered an excellent and balanced view of both Whittaker and his performance. Azeez’s comments can, on the one hand, be framed as the ribbing of a future rival, yet, whatever the motive, they highlighted the difficulty a fighter like Whittaker now faces. Stuck, not between styles but between respect and disrespect, he is in danger of thinking too much about either the criticisms of other people or the possibility of going “viral” and therefore liable to second-guess what comes naturally to him.

Against Leon Willings, for example, Whittaker began the fight all business and for two minutes resisted the usual tomfoolery by which all his pro fights have so far been defined. Then, however, he dropped Willings, got drunk on the success, and ended the first round acting rather bizarrely on his way back to his stool. It was, in a roundabout way, what people have come to expect from Whittaker: the dominance, the dancing, the display of showmanship or, to some, disrespect.

Next, an interesting thing happened. Willings, rather than fold as expected, instead grew into the contest and had success of his own. Loose like Whittaker, he had no fear of the favourite’s power and therefore started to relax, have fun, and even embarrassed Whittaker with the odd counterpunch during now-sporadic bouts of showboating.

All in all, he gained Whittaker’s respect. This was apparent at the end of the fight, when Whittaker made a point of raising Willings’ arm after the decision, and also during Whittaker’s post-fight interview, when the first thing he did was congratulate Willings on his performance. That was good to see and hear. Moreover, it was not the first time Whittaker has shown respect to an opponent after beating them.

Ben Whittaker celebrates beating Greg O’Neill on his pro debut (Lawrence Lustig)

The truth is, mimicking the inadequacies of an adversary (which Whittaker did again versus Willings) can, by definition, only ever been viewed as disrespectful. Yet that doesn’t necessarily mean the intentions are cruel. With someone like Whittaker, for instance, it’s more akin to halitosis or Tourette’s; sometimes offensive, sure, but something about which he can do very little, for it is simply his nature.

When all is said and done, whether you feel disrespected or not is something only you get to decide. Meaning: Ben Whittaker’s opponents have as much of a right to feel disrespected as Whittaker did when he heard Andy Clarke’s comments about his purported disrespect. Meaning: Andy Clarke, one of the few boxing pundits left in the UK who understands objectivity, had as much of a right to feel disrespected on camera last Friday as Ben Whittaker did when goaded by an unheralded Nigerian during a press conference. Meaning: Ben Whittaker, his opponents, and Andy Clarke all have as much of a right to feel disrespected as Emanuel Augustus when hearing Whittaker has aped his martial arts-inspired ring moniker, “The Drunken Master,” or the late Frankie Randall if he is somehow informed that Whittaker likes to calls himself “The Surgeon”.