Powell has overcome hearing impairment to become high-scoring Flyers prospect

Powell has overcome hearing impairment to become high-scoring Flyers prospect

Forward impresses on ice with ability, off ice as role model, advocate

© Linda Isenbarger

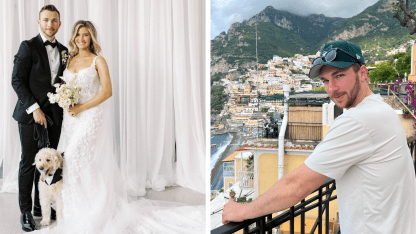

Noah Powell has faced challenges most of his life.

And the fact the 19-year-old Philadelphia Flyers forward prospect has not only taken on but overcome the many roadblocks in front of him are why he is now positioned for a career in professional hockey.

“I feel like you’ve got to lean on the people closest to you, whether that be friends, family, coaches,” Powell said, “and I’ve been fortunate enough to obviously have a very supportive family through this hockey process, and friends as well.”

Born Feb. 2, 2005, in Northbrook, Illinois, Powell began playing hockey at age 4. But a state-mandated hearing screening when Powell was in first grade diagnosed him with bilateral hearing loss, a mild to moderate hearing impairment in both ears.

His parents feared the hearing issues would end Powell’s hockey career, but instead they found the American Hearing Impaired Hockey Association (AHIHA), a Chicago-based program for hearing-impaired hockey players founded by Chicago Blackhawks Hall of Famer Stan Mikita.

“AHIHA taught us what was possible,” Powell’s mother, Maria Elena Powell, said in a 2014 story on HomeTeamsOnline.com. “It’s an amazing experience for our kids that love the game of hockey regardless of whether they are hard of hearing or deaf.”

The AHIHA clinics and camps helped Powell hone his skills and learn to compensate for his hearing loss by studying coping skills from other players and coaches with similar disabilities.

“Noah has worked hard at it,” AHIHA president Kevin Delaney said. “I’ve been coaching him since he was 8 or 9 years old, or even before that. So it’s fun to watch a player develop like that from a youth player to a young man.”

© Linda Isenbarger

That development wasn’t always easy, especially when Powell played for club teams. Hearing what coaches needed from him, communicating with teammates and referees, it all posed a challenge. Speaking up for himself wasn’t something that came naturally.

“When I was younger, it was very hard to do because it’s kind of like a blind leap of faith,” he said. “You don’t know how the coach or teacher, any setting, how they’re going to take it and if they’re going to be supportive or helpful.”

A big part of that help came from Mark Roy, Powell’s coach with the 9-year-old Illinois Jester program, in 2014. Roy, who also is hearing-impaired, was his first coach to use an assisted listening device (ALD) with Powell. Roy wore a special microphone during games that would transmit his voice directly to Powell’s hearing aids.

Rob Hutson, Powell’s coach with the 12-year-old team in the Team Illinois program, provided a different kind of motivation.

Hutson, the father of Montreal Canadiens defenseman Lane Hutson and Washington Capitals defenseman prospect Cole Hutson, also wore the ALD during games but made no other accommodations for Powell.

“He was a no-BS kind of coach,” Powell said. “So it was like, you’re there doing what you need to do or you’re not. And if you’re not doing what you need to do, you’re not going to play.

“So I needed to kind of go up to him and initiate that. I made sure I could get the information so I could go do what I needed to do. He was very supportive … a very, very helpful guy. That’s when I kind of brought it into the classroom a little more because I struggled a little with that teacher setting and he was like, ‘Well, you can’t just do it on the ice. You’ve got to do it in all aspects of your life.’ “

Powell credits Hutson for forcing him to learn to advocate for himself, which helped him mature on and off the ice. To this day, Powell refers to Hutson as the most influential coach he has had.

“He needs a little longer runway to get to where he’s at because of the challenges of the hearing,” Hutson said, “but he won’t make that as an excuse, and I won’t make it as an excuse for him.

“I always want more as a coach and as a dad and as somebody that’s involved in hockey. I want to push the players and my own boys harder and harder. Noah is lucky enough to understand that when he pushes, he’s actually getting some reward.”

© Philadelphia Flyers

Powell no longer wears hearing aids when he’s on the ice, instead relying on his ability to read lips and willingness to speak up as needed.

“It’s advocating for yourself,” he said, “telling your teammates, making sure they know, the coaching staff, the training staff, and then kind of putting yourself in situations where you can make sure you’re getting the most out of what people are saying and always making sure you’re facing whoever’s talking to you.”

It’s why Powell’s coaches and trainers now don’t always notice his hearing impairment.

“I knew about [the hearing loss] but it’s never been an issue on the ice with him,” said former NHL player Ben Eager, who has trained Powell during the offseason for about seven years at his Jet Hockey Training Arena in Glenview, Illinois. “I know he’s dealt with it; I know he reads lips, but I’ve really never had to think about it too much. I know it’s definitely an issue for him, but it’s never really held him back.”

But his production on the ice did hold him back. He had 19 points (eight goals, 11 assists) in 53 games in 2022-23, his first season with Dubuque of the United States Hockey League, and was passed over in all seven rounds of the 2023 NHL Draft.

Powell’s struggles continued into last season, whean he scored one goal for Dubuque in his first 16 games.

“His whole time with us in Dubuque, we all felt like he had another gear in terms of actually executing in games,” team assistant coach Evan Dixon said. “… He was great in training camp, he’s a really strong kid. Really good through the preseason, then the first couple games in the year was a little rocky.

“Took us all a second to regroup and kind of really not define, but get him headed on the right path. For him, that was largely directed toward his strengths as a player. He’s really strong, he can protect pucks well, he’s got a hard shot. For us it was just being consistent with the message of how he can get into areas to be a scoring threat offensively.

“We had some conversations with him and video sessions with him that were always geared toward that. I won’t say one particular meeting clicked, but there was a moment that he bought into it fully and started to see results in a big way.”

After that slow start last season, Powell scored 42 goals in his final 45 games, and finished with a USHL-leading 43 goals in 61 games.

The Flyers were among the teams that took notice, and selected Powell (6-foot-1, 201 pounds) in the fifth round (No. 148) of the 2024 NHL Draft.

“You can see how he can score goals in juniors, just because of his strength on the puck, his ability to shoot the puck, his willingness to go to the hard areas and get his nose in there,” Flyers assistant general manager Brent Flahr said. “A real determined kid. He’s just one of those kids that the puck just follows. Whether it’s hockey sense or whatever it is, the puck follows him and he gets his looks at the net and he’s willing to pay a price and get his nose in there to score goals.”

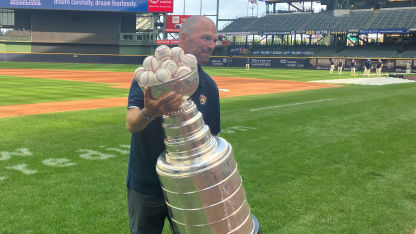

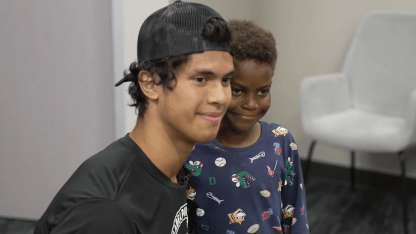

Powell will continue his development this fall as a freshman at Ohio State, while also being a role model for hearing-impaired youth hockey players. During a busy offseason that included Flyers development camp, the 2024 World Junior Summer Showcase and preparing for college, he skated at an AHIHA camp, and met with 7-year-old Howard James, a hearing-impaired player in the Snider Hockey program.

© Philadelphia Flyers

“I feel like in a sense, you’re always playing for something bigger than yourself,” he said. “There were role models there for me, and hopefully, I can be a role model for some of those kids.”

Delaney said Jim Kyte, a defenseman who was deaf but played 13 NHL seasons from five teams from 1982-96, was a role model for him growing up. He believes Powell could do for the next generation what Kyte did for him.

“He came in in the middle of the week and participated in practices, he went out with the younger teams, he shot on the goalies,” Delaney said of Powell. “He really got involved in helping out and being a mentor. … Noah has realized, ‘I can help, I can make an impact showing these kids, Look, you love the game, you want to work hard, you can be in the same place I am 10 years from now.’ “

© Linda Isenbarger

He also could be a role model by eventually reaching the NHL.

“The sky’s the limit for him,” Dixon said. “He’s got a really good hockey brain, he’s understands the game … physically he’s very gifted, he’s stronger than just about all of his peers. He’s built like a statue. He’s got an ability to be a powerful force on the ice.

“He’s a guy that if you need a big hit, he can lay a big hit. You need somebody to score a goal, he’s got the ability to go do that. He’s a presence on the ice and I think he’s only going to continue to improve his ability and hopefully have those same traits line up for him to have that same kind of impact at the NHL level.”